Does Clarivate understand what citations are for? / Hugh Rundle

A month ago Clarivate announced a new yet-to-be-released product called Nexus: "Clarivate Nexus acts as a bridge between the convenience of AI and the rigor of academic libraries". This is a pitch to librarians who have correctly identified generative AI chatbots as purveyors of endless bullshit, but also know that students and some researchers are going to use them anyway. Clarivate tells us that we can patch up the fabrications of chatbots with reassuring terms like "trusted sources", "verified academic references", and "authoritative".

Looking more carefully at Clarivate's marketing material, what they are proposing suggests that Clarivate understands neither what citations are for nor why fabricated citations are a problem. This is somewhat surprising for the company that controls and manages such key parts of the scholarly publishing systems as the citation database Web of Science, scholarly publishing and indexing company ProQuest, and the Primo/Summon Central Discovery Index.

Why we cite

It can get a little more complicated than this, but there are essentially two reasons for citations in scholarly work.

The first is to indicate where you got your data. If I write that the population of Australia in June 2025 was 27.6 million people, I need to back up this claim somehow. In this case, I would cite the Australian Bureau of Statistics as the source. This adds credibility to a claim by enabling readers to check the original source and assess whether it actually does make the same claim, and whether that claim is credible. If I said that the population of Australia in 2025 was 100 million people and cited a source which made that claim and in turn cited the ABS as their source, you could follow the chain of references back and identify that the paper I cited is where the error ocurred.

The second reason we cite a source is to give credit for a concept, term, or model for thinking. This is less about checking facts and more about academic norms and manners, though it also indicates how credible a scholar might be in terms of their understanding of a field. For example I might describe a concept whereby librarians feel that the mission of libraries is good and righteous, and this leads to burnout because they feel they can never complain about their working conditions. If I did not cite Fobazi Ettarh's Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves whilst describing this, I would rightly not be seen as a credible scholar in the field, or alternatively might be seen as surely knowing about Ettarh's work but deliberately ignoring it or even claiming her work as my own idea.

Why fabricated citations are bad

So that's the basics of why scholars include citations in their work. We can now explore why fabricated citations are a problem. There are two related but distinct reasons.

Citations that look real but are actually fake waste the time of already-busy library resource-sharing teams by making them spend time checking whether the citation is real, and sometimes looking for items that don't exist. This aspect of fabrication is bad because the cited item doesn't exist. If we match this to our first reason for citing, we can see that a claim that is backed by a citation to nothing at all is, uh, pretty problematic if the reason we cite is to link to the source data backing up a claim. It's equivalent to simply not providing a citation at all, except worse because we're claiming that our plucked-out-of-the-air "fact" is backed up by some other source.

The second problem with fabricated citations is that there is no connection between the statement being made and the source being cited. Even if the source being cited exists, the connection between the statement and the cited item is fabricated. This is slightly more difficult to understand because generative AI is based on probability, so in many cases there will appear to be a connection. But without a tightly-controlled RAG system, it's likely to simply be a lucky guess. The problem here is one of academic integrity – we've cited a source that exists, but it may or may not back up our claim, and the claim doesn't follow from the source.

A false nexus

Clarivate seems to be conflating these two issues. Their Nexus product has two core functions: checking citations to see if they are real, and suggesting references for content in chatbot conversations. The first is genuinely useful, though highly constrained – Clarivate only checks their own indexes, and defines anything that doesn't appear in those indexes as either non-existing, or "non-scholarly" (it's unclear how it would define, for example, something with a DOI that exists but doesn't appear in Web of Science). Neither academia nor the tech industry are short on hubris, but even in that context, "anything not listed in our proprietary databases isn't credible" is a pretty eyebrow-raising claim.

The second function kicks in when the citation checker defines a citation as failed – it offers to "Find Verified Alternative". That is, Nexus offers to replace both cited sources that don't exist and cited sources that "aren't scholarly" with another real source. This addresses the first problem (cited sources that don't exist) but not the second (cited sources that aren't the real source of a claim or quotation).

With Nexus, Clarivate are essentially integrity-washing synthetic text, giving it an academic sheen without any academic rigour. Far from helping librarians, Clarivate's Nexus threatens to further unravel the hard work we do to teach students information literacy skills and its sparkling variety, "AI literacy". Students are already inclined to write their argument first and go on a fishing expedition for citations to back it up later (I certainly wrote my undergraduate essays this way). The last thing we want to do is direct them to a product that encourages this academically dishonest behaviour.

ChatGPT is designed to provide something that looks like a competent answer to a question. Nexus seems to be designed to amend this answer-shaped text into something that looks like a correctly-cited academic essay. But the point of student assessments isn't to produce essays – it's to produce competent researchers and systematic thinkers. Perhaps Clarivate thinks there is a large potential market of universities who want to help their own students cheat on assignments in ways that look more credible. To that, I would say "[citation needed]".

Memorial for Fobazi Ettarh / In the Library, With the Lead Pipe

It is with heavy hearts and great sadness that we acknowledge the passing of trailblazer and fire-starter Fobazi Ettarh. Her loss will be felt by us all for years to come.

Fobazi published two articles with us at ITLWTLP. In 2014 she wrote “Making a New Table: Intersectional Librarianship,” one of the first scholarly articles published about viewing librarianship through an intersectional lens. In 2018 she published the hugely influential “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves.” Since then, we have published many, many articles that cite the concept she identified: vocational awe. She was, to borrow a phrase from bell hooks, a maker of theory and a leader of action. We remember her as one of the great thinkers of her time, and we encourage our readers to spend some time with her words and her work. Additionally, please consider contributing to or sharing the link for her GoFundMe.

Streamlining Open Access Agreement Lookup for U-M Authors / Library Tech Talk (U of Michigan)

Open Access (storefront) by Gideon Burton is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Tesla's Not-A-Robotaxi Service / David Rosenthal

|

| Source |

Fred Lambert has two posts illustrating the distance between Musk's claims and reality. Below the fold I look at both of them:

"Safety monitors" less safe than "drivers"

First, Tesla ‘Robotaxi’ adds 5 more crashes in Austin in a month — 4x worse than humans:Tesla has reported five new crashes involving its “Robotaxi” fleet in Austin, Texas, bringing the total to 14 incidents since the service launched in June 2025. The newly filed NHTSA data also reveals that Tesla quietly upgraded one earlier crash to include a hospitalization injury, something the company never disclosed publicly.Even before they were changed, we knew very few of the details:

As with every previous Tesla crash in the database, all five new incident narratives are fully redacted as “confidential business information.” Tesla remains the only ADS operator to systematically hide crash details from the public through NHTSA’s confidentiality provisions. Waymo, Zoox, and every other company in the database provide full narrative descriptions of their incidents.But what we do know isn't good:

With 14 crashes now on the books, Tesla’s “Robotaxi” crash rate in Austin continues to deteriorate. Extrapolating from Tesla’s Q4 2025 earnings mileage data, which showed roughly 700,000 cumulative paid miles through November, the fleet likely reached around 800,000 miles by mid-January 2026. That works out to one crash every 57,000 miles.The numbers aren't just not good, they're apalling:

By the company’s own numbers, its “Robotaxi” fleet crashes nearly 4 times more often than a normal driver, and every single one of those miles had a safety monitor who could hit the kill switch. That is not a rounding error or an early-program hiccup. It is a fundamental performance gap.There are two points that need to be made about how bad this is:

- However badly, Tesla is trying to operate a taxi service. So it is misleading to compare the crash rate with "normal drivers". The correct comparison is with taxi drivers. The New York Times reported that:

In a city where almost everyone has a story about zigzagging through traffic in a hair-raising, white-knuckled cab ride, a new traffic safety study may come as a surprise: It finds that taxis are pretty safe.

A law firm has a persuasive list of reasons why this is so. So Tesla's "robotaxi" is actually 6 times less safe than a taxi.

So are livery cars, according to the study, which is based on state motor vehicle records of accidents and injuries across the city. It concludes that taxi and livery-cab drivers have crash rates one-third lower than drivers of other vehicles. - Fake Self Driving is a Level 2 system that requires a human behind the wheel, and that is the way Tesla's service in California has to operate. But in Austin the human is in the passenger seat, or in a chase car. Tesla has been placing bystanders at risk by deliberately operating in a way that it knows, and the statistics it reports show, is unsafe.

Tesla's Catch-22

Second, Tesla admits it still needs drivers and remote operators — then argues that’s better than Waymo:Tesla filed new comments with the California Public Utilities Commission that amount to a quiet admission: its “Robotaxi” service still relies on both in-car human drivers and domestic remote operators to function. Rather than downplaying these dependencies, Tesla leans into them — arguing that its multi-layered human supervision model is more reliable than Waymo’s fully driverless system, pointing to the December 2025 San Francisco blackout as proof.Tesla's filing admits that the service they market as a "robotaxi" really isn't one:

The filing, submitted February 13 in CPUC Rulemaking 25-08-013, reveals the massive operational gap between what Tesla calls a “Robotaxi” and what Waymo actually operates as one.

Tesla operates its service using TCP (Transportation Charter Party) vehicles equipped with FSD (Supervised), a Level 2 ADAS system that, by definition, requires a licensed human driver behind the wheel at all times, actively monitoring and ready to intervene.Compare this with a Waymo:

On top of that in-car driver, Tesla describes a parallel layer of remote operators. The company states it employs domestically located remote operators in both Austin and the Bay Area, and that these operators are subject to DMV-mandated U.S. driver’s licenses, “extensive background checks and drug and alcohol testing,” and mandatory training. Tesla frames this as a redundancy system, remote operators in two cities backing up the in-car drivers.

That’s two layers of human supervision for a service Tesla markets as a “Robotaxi.”

Waymo’s vehicles have no driver in the car. Waymo uses remote assistance operators who can provide guidance to vehicles in ambiguous situations, but the vehicle drives itself. Waymo’s remote operators don’t control the car, they confirm whether it’s safe to proceed in edge cases like construction zones or unusual road conditions.This is where Tesla's marketing their service as a "robotaxi" creates a Catch-22:

... Tesla’s system requires a human to drive the car and has remote operators as backup. Waymo’s system drives itself and has remote operators as backup. Tesla is essentially describing a staffing-intensive taxi service with driver-assist software. Waymo is describing an autonomous transportation network.

Tesla argues forcefully that its Level 2 ADAS vehicles should remain outside the scope of this AV rulemaking entirely, agreeing with Lyft that they aren’t “autonomous vehicles” under California law.But note that:

At the same time, Tesla is fighting Waymo’s proposal to prohibit Level 2 services from using terms like “driverless,” “self-driving,” or “robotaxi.” Tesla calls this proposal “wholly unnecessary,” arguing that existing California advertising laws already cover misleading marketing.

A California judge already ruled in December 2025 that Tesla’s marketing of “Autopilot” and “Full Self-Driving” violated the state’s false advertising laws.So here is the Catch-22:

Tesla is telling regulators its vehicles are not autonomous and require human drivers, while simultaneously fighting for the right to keep calling the service a “Robotaxi.” Tesla wants the legal protections of being classified as a supervised Level 2 system and the marketing benefits of sounding like a fully autonomous one.Sadly, this is just par for the course when it comes to Tesla's marketing. Essentially everything Elon Musk has said about not just the schedule but more importantly the capabilities of Fake Self Driving has been a lie, for example a 2016 faked video. These lies have killed many credulous idiots, but they have succeeded in pumping TSLA to a ludicrous PE ratio because of the kind of irresponsible journalism Karl Bode describes in The Media Can't Stop Propping Up Elon Musk's Phony Supergenius Engineer Mythology:

One of my favorite trends in modern U.S. infotainment media is something I affectionately call "CEO said a thing!" journalism.After all, if a journalist does include an expert pointing out that the CEO is bullshitting:

"CEO said a thing!" journalism generally involves a press outlet parroting the claims of a CEO or billionaire utterly mindlessly without any sort of useful historical context as to whether anything being said is factually correct.

There's a few rules for this brand of journalism. One, you can't include any useful context that might shed helpful light on whether what the executive is saying is true. Two, it's important to make sure you never include a quote from an objective academic or expert in the field you're covering that might challenge the CEO.

statements produced without particular concern for truth, clarity, or meaningthe journalist will lose the access upon which his job depends. But I'm not that journalist, so here is my list of the past and impending failures of the "Supergenius Engineer":

- weird pickup trucks

- self-driving cars

- robotaxis

- hyperloop

- tunneling

- brain interfaces

- humanoid robots

- Mars colonization

- Moon landing

- Tesla's cars: Wikipedia notes that:

Tesla was incorporated in July 2003 by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning as Tesla Motors. ... In February 2004, Elon Musk led Tesla's first funding round and became the company's chairman, subsequently claiming to be a co-founder

Starting in 2008, Franz von Holzhausen designed the Model S, which launched in 2012 and was Tesla's first success. Initially, Tesla was a great success, but it has failed to update its line-up. It is now far behind Chinese EV manufacturers and losing market share worldwide. They will lose the US market share once the Chinese set up US factories. - Space X Falcon 9: Musk's insight that re-usability would transform the space business was a huge success. It was thanks to significant government support and a great CEO, Gwynne Shotwell.

2026-02-24: The 10th Computational Archival Science (CAS) Workshop Trip Report / Web Science and Digital Libraries (WS-DL) Group at Old Dominion University

|

| IEEE BigData 2025-The10th Computational Archival Science (CAS) Workshop Home Page |

The 10th Computational Archival Science (CAS) Workshop is part of 2025 IEEE Big Data Conference (IEEE BigData 2025). It was an online workshop held on Tuesday December 9, 2025. It included close to 70 participants, with a keynote from Dr. Phang Lai Tee, National Archives of Singapore and Chair of the UNESCO Memory of the World Preservation Sub-Committee on Artificial Intelligence, and 18 papers from 27 institutions in 8 countries spanning 5 continents: Canada, USA (North America) / Brazil (South America) / Scotland, Spain, Switzerland (Europe) / South Africa (Africa) / Korea (Asia).

Michael Kurtz, who passed on December 17th, 2022 launched the CAS initiative in 2016, with Victoria Lemieux, Mark Hedges, Maria Esteva, William Underwood, Mark Conrad, and Richard Marciano.

The 10th CAS workshop was organized by the CAS Workshop Chairs:

- Mark Hedges from King’s College London UK

- Victoria Lemieux from U. British Columbia CANADA

- Richard Marciano from U. Maryland USA

The workshop started with a 10 minute welcome message from the CAS workshop chairs and then a 20 minute keynote from Dr. Phang Lai Tee, National Archives of Singapore, who presented "Applications and Challenges for Archives and Documentary Heritage in the Age of AI: Some Reflections". Overall, the topic is a timely reflection on how AI is reshaping archival and documentary heritage work, highlighting both opportunities and challenges. It was a strong presentation that included emphasis on practical challenges such as scale, access, cybersecurity, and regulation.

The workshop itself was divided into six sessions:

1: Blockchain & Archives [2 papers]

A. Blockchain and Responsible AI: Enhancing Transparency, Privacy, and Accountability through Blockchain Hackathon

Authors: Jiho Lee, Jaehyung Jeong, Victoria Lemieux,Tim Weingartner, and JaeSeung Song

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe presentation highlights a curriculum initiative where participants used a blockchain-enabled fair-data ecosystem (Clio-X) in Blockathon to build privacy-preserving AI chatbots for archival datasets. It highlights blockchain’s potential to improve transparency and accountability in AI workflows by making all actions traceable on-chain.

B. Cryptographic Provenance and AI-generated Images

Authors: Jessica Bushey, Nicholas Rivard, and Michel Barbeau

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe presentation highlighted how content credentials and cryptographic provenance frameworks can operationalize archival trustworthiness for born-digital assets and AI-generated images by embedding tamper-evident metadata into assets, which is a highly relevant and timely challenge given the proliferation of synthetic media. It effectively bridges archival theory (authenticity and provenance) with practical systems and discusses how blockchain and content credentials can support verifiable history of digital images, situating the work within computational archival science. Overall, it makes a strong conceptual and methodological contribution to trustworthy preservation of digital content.

2: Processing Analog Archives [4 papers]

A. Using an Ensemble Approach for Layout Detection and Extraction from Historical Newspapers

Authors: Aditya Jadhav, Bipasha Banerjee, and Jennifer Goyne

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe presentation focused on layout detection and Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for historical newspapers by proposing a modular, detector-agnostic ensemble pipeline combining OpenCV, Newspaper Navigator, and a fine-tuned TextOnly-PRIMA model to improve segmentation and extraction on variable scans. It’s strong in engineering detail and demonstrates practical improvements over commercial baselines like AWS Textract, especially on degraded material. Overall, it’s a solid methodological contribution with clear application value in large-scale digitization efforts.

B. PARDES: Automatic Generation of Descriptive Terms for Logical Units in Historical Handwritten Collections

Authors: Josepa Raventos-Pajares, Joan Andreu Sanchez, and Enrique Vidal

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe PARDES project presents a practical and scalable method for automatically generating descriptive terms from noisy handwritten text recognition (HTR) outputs in large historical collections, using probabilistic indexing and Zipf's Law to identify important terns. It’s strong in handling uncertainty in HTR.

C. From Analog Records to Computational Research Data: Building the AI-Ready Lab Notebook

Authors: Joel Pepper, Zach Siapno, Jacob Furst, Fernando Uribe-Romo, David Breen, and Jane Greenberg

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESSimilar to the previous presentation, this one addressed transforming analog, handwritten lab notebooks into AI-ready digital data to unlock valuable experimental records for computational analysis. It demonstrated promising performance. Overall, it’s a good step toward making analog scientific records computationally accessible and usable for AI systems.

D. Classification of Paper-based Archival Records Using Neural Networks

Authors: Jussara Teixeira, Juliana Almeida, Tania Gava, Raphael Lugon Campo Dall’Orto, and Jose M´ arcio Moraes Dorigueto

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe presentation demonstrates a practical application of supervised machine learning (ML) to classify unprocessed archival records, achieving high accuracy and scalability on a large real-world governmental dataset (Electronic Process System (SEP) of the State of Espirito Santo, Brazil). It effectively shows how a modular ML architecture can be integrated into existing archival systems, and how clustering similar records can reduce manual effort. Overall, it’s a solid empirical case study of ML enhancing a core archival function at scale.

3: Retrieval-augmented Generation [3 papers]

A. Developing a Smart Archival Assistant with Conversational Features and Linguistic Abilities: the Ask_ArchiLab Initiative

Authors: Basma Makhlouf Shabou, Lamia Friha, and Wassila Ramli

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis talk presented a compelling initiative to modernize archival practice by building a conversational AI assistant that integrates advanced Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and semantic technologies to support fast, contextual, and professional‑level archival queries. It’s strong in conceptualizing how multilingual conversational agents can bridge gaps in access, complex metadata, and diverse user expertise. Overall, it’s an innovative approach with great potential to enhance usability and knowledge discovery in digital archives.

B. Index-aware Knowledge Grounding of Retrieval-Augmented Generation in Conversational Search for Archival Diplomatics

Authors: Qihong Zhou, Binming Li, and Victoria Lemieux

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis work presents an index‑aware chunking strategy to improve RAG pipelines for conversational search by grounding retrieval on structured index terms extracted from PDFs, aiming to reduce resource demands, accuracy issues, and hallucinations common in standard RAG workflows. It’s a practical contribution that addresses problems with traditional chunking strategies. Overall, it is an interesting methodological refinement with promising implications for archival conversational search but would benefit from broader validation.

C. Retrieval-augmented LLMs for ETD Subject Classification

Authors: Hajra Klair, Fausto German, Amr Ahmed Aboelnaga, Bipasha Banerjee, Hoda Eldardiry, and William A. Ingram

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis work presents a two‑stage RAG‑based pipeline that uses keyword extraction and guided question generation from Electronic Theses and Dissertations (ETD) abstracts to retrieve and synthesize core document content, tackling the challenge of long, full‑text processing. It addresses the challenge of subject classification at scale for ETD by capturing signatures that go beyond simple lexical similarity to improve classification accuracy and contextual richness. The evaluation shows improvements over traditional approaches. Overall, it’s a promising and well‑structured application of RAG methods to a real-world problem.

4: Archival Theory & Computational Practice [4 papers]

A. Archival Research Theory: Putting Smart Technology to Work for Researchers

Authors: Kenneth Thibodeau, Alex Richmond, and Mario Beauchamp

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis work extends archival theory beyond traditional archival management to a new Archival Research Theory (ART) framework that models archives as complex informational systems with informative potential responsive to researchers’ questions, grounded in semiotics, Constructed Past Theory, and type theory. It’s conceptually rich, offering a strong theoretical foundation for integrating smart technologies into archival research and emphasizing how meaning and context can be formally modeled to support diverse inquiry. Overall, it makes a thoughtful and potentially foundational contribution to bridging archival theory and computational practice.

B. Systems Thinking, Management Standards, and the Quest for Records and Archives Management Relevance

Author: Shadrack Katuu

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThe presentation makes a case for records and archives management (RAM) within organizations by embedding RAM into widely adopted Management System Standards (MSS) like ISO frameworks, which currently drive visibility and measurable outcomes in areas such as quality and security. It uses systems thinking and standards practice to argue that RAM can gain institutional relevance and leadership buy‑in by aligning with structured MSS processes and the Plan‑Do‑Check‑Act cycle, thereby elevating archival functions beyond marginal roles. Overall, it’s a good management‑focused contribution that highlights the importance of standards and systemic framing for advancing archival relevance.

C. Can GPT-4 Think Computationally about Digital Archival Practices?

Authors: William Underwood and Joan Gage

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis work investigates whether GPT‑4o demonstrates computational thinking capabilities applied to digital archival tasks, grounding the analysis in a recognized computational thinking taxonomy. It surfaces compelling examples where the model exhibits knowledge across archival processes and computational practices, suggesting its potential as a learning partner or assistant in teaching archival computational methods. Overall, the paper offers a thought‑provoking exploration of LLM capabilities in a computational archival context, with promising avenues for further research.

D. Algorithm Auditing for Reliable AI Authenticity Assessment of Digitized Archival Objects

Author: Daniel F. Fonner

PAPER — VIDEO —SLIDESThis presentation shows how small variations in input image resolution can drastically affect AI‑based art authentication results, highlighting a key vulnerability in applying such models to archival or cultural heritage objects and raising important concerns about reliability and manipulation risk. It makes a strong case that algorithm auditing should be embedded in computational archival science practices to improve transparency, reproducibility, and accountability of automated analyses. Overall, it’s a practical contribution that urges the need for rigorous evaluation frameworks when deploying AI for authenticity and provenance tasks in digital archives.

5: Knowledge Organization & Retrieval [2 papers]

A. Ontologies Applied to Archival Records: a Preliminary Proposal for Information Retrieval

Authors: Thiago Henrique Bragato Barros, Maurício Coelho da Silva, Rafael Rodrigo do Carmo Batista, David Haynes, and Frances Ryan

PAPER — VIDEO — The slides were not postedThis paper presents an ontology‑driven approach to improve information retrieval (IR) over archival descriptions and digital objects by capturing archival contexts such as provenance, functions, agents, and events within a formal semantic model. It grounds its design in established ontology engineering and archival principles to support semantic indexing, reasoning, and query handling. Overall, it makes a decent conceptual contribution toward ontology‑enhanced archival IR.

B. Operationalizing Context: Contextual Integrity, Archival Diplomatics, and Knowledge Graphs

Authors: Jim Suderman, Frédéric Simard, Nicholas Rivard, Iori Khuhro, Erin Gilmore, Michel Barbeau, Darra Hofman, and Mario Beauchamp

PAPER — VIDEO — SLIDESThis paper lays out a context‑driven privacy framework for archival records that combines theories of contextual integrity, archival diplomatics, and knowledge graphs to make privacy‑relevant relationships machine‑legible and support informed decisions about sensitive information at scale. Its strength lies in operationalizing context rather than content alone using GraphRAG and knowledge graphs to capture nuanced contextual features that traditional vector embeddings miss, thereby offering a richer basis for privacy assessment. Overall, it’s a promising conceptual and advancement toward AI‑enabled privacy support in archives.

6: Web Archiving [3 papers]

This session highlights my contributions. The workshop designated two slots for my papers. The first slot was for presenting one of the papers and the second one is for summarizing the remaining two papers, which is why there are three papers, but only two videos. The slides for both slots are combined in one file. I want to thank Richard Marciano, Victoria Lemieux, and Mark Hedges for giving me the opportunity to present and being flexible with the workshop registration since my work is not funded and we were unable to pay the registration fees.

A. Arabic News Archiving is Catching Up to English: A Quantitative Study

In the first paper, I presented a quantitative analysis of web archiving coverage for Arabic versus English news content over a 23‑year period, revealing that while English pages are still archived at a higher rate, Arabic archival coverage has increased significantly in recent years. I showed the heavy dependence on the Internet Archive (IA) for web archiving and that other public web archives contribute very little, exposing a centralization risk where loss of IA would make most archived content inaccessible. This paper is a continuation of previous work "Comparing the Archival Rate of Arabic, English, Danish, and Korean Language Web Pages".

B. The Gap Continues to Grow Between the Wayback Machine and All Other Web Archives

PAPER

The second paper I presented highlights a quantitative study showing that the Internet Archive (IA) overwhelmingly dominates public web archiving, preserving 99.74 % of archived Arabic and English news pages in the dataset I constructed (1.5 million URLs) while all other web archives combined account for only a tiny fraction. I highlighted the risk to web archiving if the IA became unavailable, the vast majority of archived online news would be lost or irretrievable, underscoring a critical vulnerability in web preservation. My analysis offer clear results, but the paper could benefit from a broader discussion of why other web archives are shrinking and what practical strategies could diversify preservation efforts. Overall, it is an important wake‑up call about concentration in web archiving and the fragility of our collective digital memory. This paper is a continuation of previous work "Profiling web archive coverage for top-level domain and content language".

C. Collecting and Archiving 1.5 Million Multilingual News Stories’ URIs from Sitemaps

The third paper I presented introduced JANA1.5, a large dataset of 1.5 million Arabic and English news story URLs collected from news site sitemaps, and demonstrated an effective sitemap‑based collection method that outperforms alternatives like RSS, X (formerly Twitter), and web scraping. I also discussed ways for noise reduction. I ended with explaining how this dataset is going to be submitted to the IA.

One of the standout aspects of the CAS workshop was its responsiveness and quick turnaround. Reviewers' comments were actionable and came back quickly, decisions were clear, and the entire process moved at a fast pace that made it possible to focus on the work itself rather than waiting on it. The entire process from submission to publishing and presenting the work takes about a month. It’s the kind of efficiency every venue should strive for. Attending the 10th CAS Workshop was great. It underscored issues related to computational archival science including centralization, authenticity, and who gets to be remembered. It was a rewarding experience to present my work at the CAS workshop exploring web archiving’s dependence on the Internet Archive. The discussion highlighted just how vital the Internet Archive is to our digital memory, and it was inspiring to see how their work motivates us all to take action and contribute to preserving our online heritage.

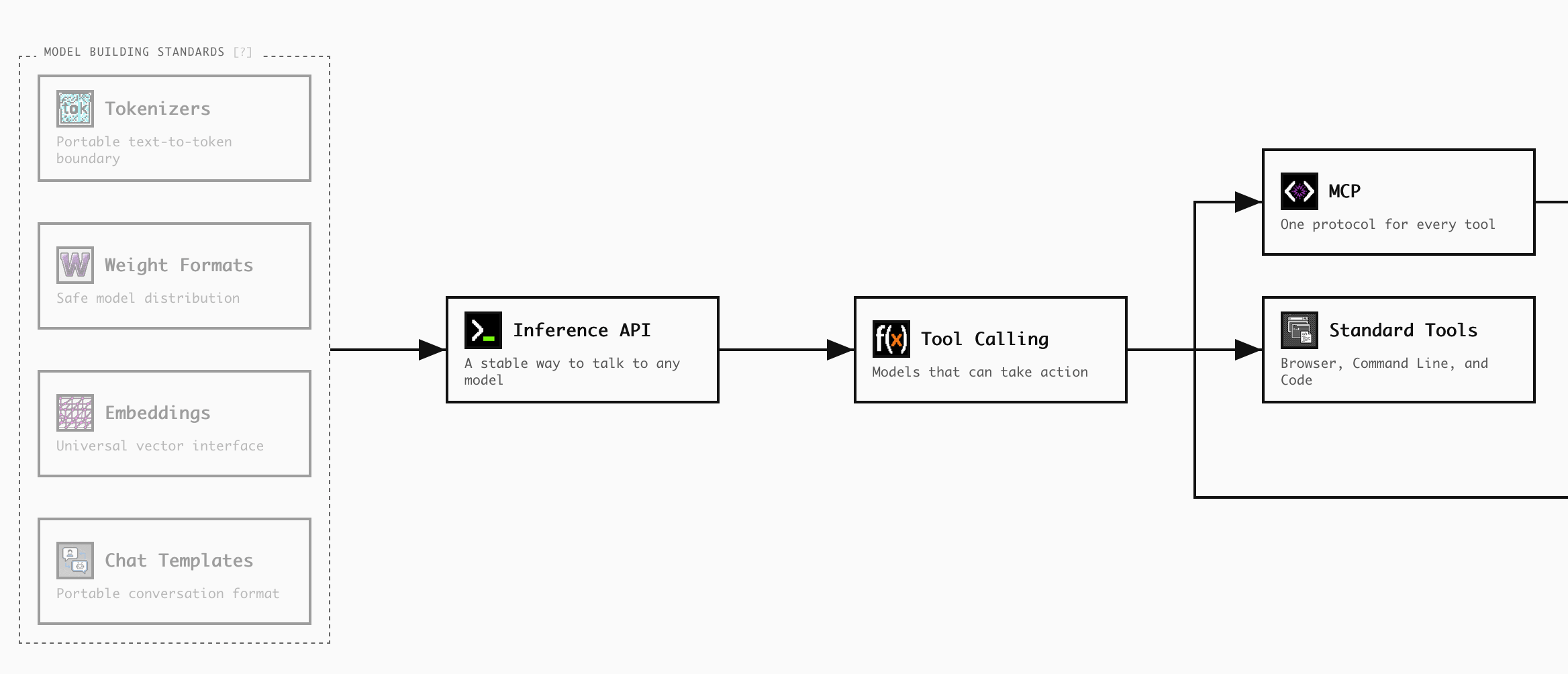

Launching the Agent Protocols Tech Tree / Harvard Library Innovation Lab

Today I am sharing the Agent Protocols Tech Tree. APTT is a visual, videogame-style tech tree of the evolving protocols supporting AI agents.

Where did this come from?

I made the APTT for a session on “The Role of Protocols in the Agents Ecosystem” at the Towards an Internet Ecosystem for Sane Autonomous Agents workshop at the Berkman Klein Center on February 9th.

It’s a video game tech tree because, while the word “protocols” is boring, the phenomenon of open protocols is fascinating, and I want to make them easier to approach and explore.

What is an open protocol? Why care about them?

An open protocol is a shared language used by multiple software projects so they can interoperate or compete with each other.

Protocols offer an x-ray of an emerging technology — they tell you what the builder community actually cares about, what they are forced to agree on, what is already done, and what is likely to come next.

Open protocols go back to the founding of the internet when basic concepts like “TCP/IP” were standardized — not by a government or company creating and enforcing a rule, but by a community of builders based on “rough consensus and running code.” On the internet no one could force you to use the same standards as everyone else, but if you wanted to be part of the same conversation, you had to speak the same language. That created strong incentives to agree on protocols, from SMTP to DNS to FTP to HTTP to SSL. By tracing each of those protocols, you could see the evolving concerns of the people building the internet.

(For a great discussion of that history, see “The Battle of the Networks” from LIL faculty director Jonathan Zittrain’s book “The Future of the Internet — and How to Stop It.”)

Why are protocols so important for AI agents?

Like the early internet, AI agents today are an emerging, distributed phenomenon that is changing faster than even experts can understand. We’re holding workshops with names like “Towards an Internet Ecosystem for Sane Autonomous Agents” because no one really knows what it will mean to have millions of semi-autonomous computer programs acting and interacting in human-like ways online.

Also like the early internet, it’s tempting to look for some government or company that is in charge and can tame this phenomenon, set the rules of the road. But in many ways there isn’t one. The ingredients of AI agents are just not that complex or that controlled.

This makes sense if you look at Anthropic’s definition of an agent, which is simply “models using tools in a loop.” That is not a complex recipe: it requires a large language model, of which there are now many, including powerful open source ones that can run locally; a fairly small and simple control loop; and a set of “tools,” simple software programs that can interact with the world to do things like run a web search or send a text message. “Agents” as a phenomenon are a technique, like calculus, not a service, like Uber.

That makes agents hard to regulate, and makes protocols incredibly important. It is protocols that give agents the tools they use. It is protocols that the builder community are developing as fast as they can to increase what agents can do. If you want to nudge this technique toward human thriving, it is protocols that might most shape agent behavior by making some agents easier to build than others.

To be sure, protocols aren’t the only way to influence technological development. Larry Lessig’s classic “pathetic dot theory” outlines markets, laws, social norms, and architecture as four separate ways that individual action gets regulated, and protocols are just an aspect of architecture. But the more a technology is dispersed and simple to recreate, the more protocols come into play in how it evolves.

How do I use the APTT?

APTT is designed to be helpful whether you’re a less-technical person who just wants to understand what agents are, or a more technical person who wants to understand exactly what’s getting built.

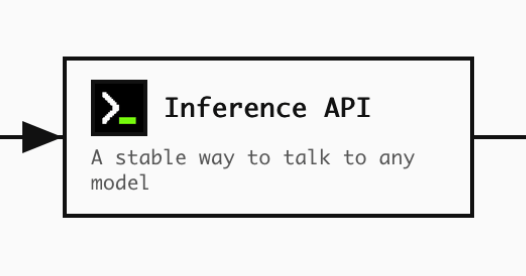

Either way the pile of agent technologies is confusing, so I recommend starting at the beginning with “Inference API.”

Video games are often designed so you start with a simple feature unlocked and then progressively unlock more and more complex options as you learn the game. The same approach works here: imagine that you have just unlocked “Inference API” in this game, and once you’re comfortable with that, explore off to the right to see how each protocol enables or necessitates the next.

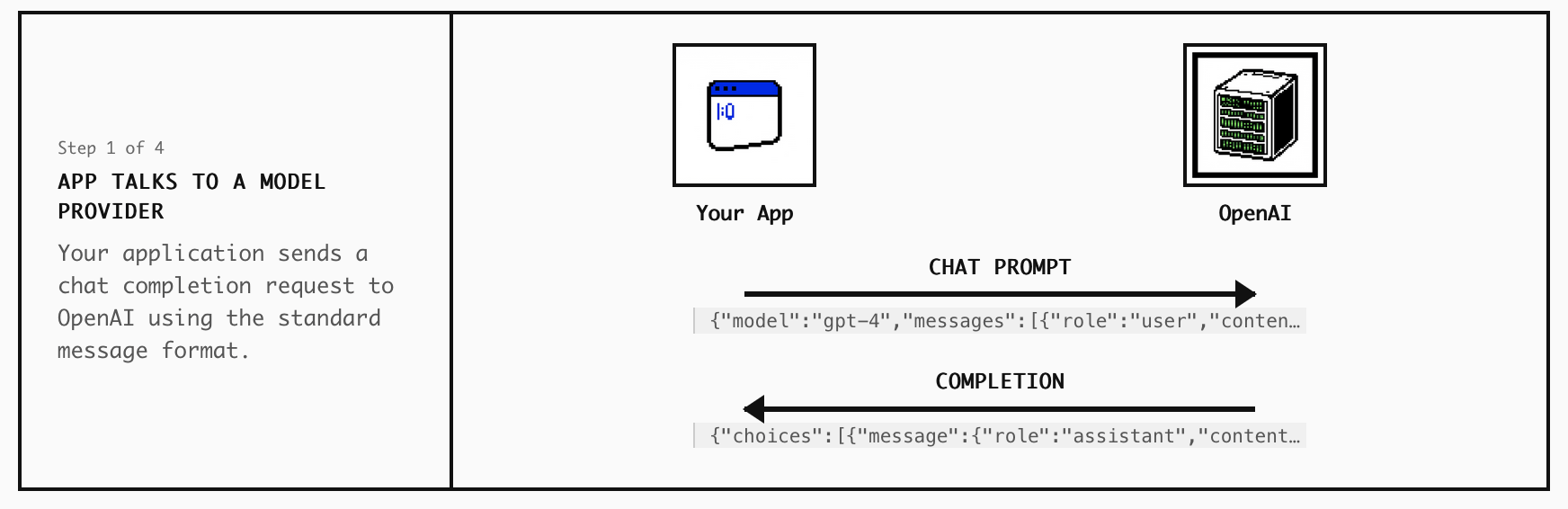

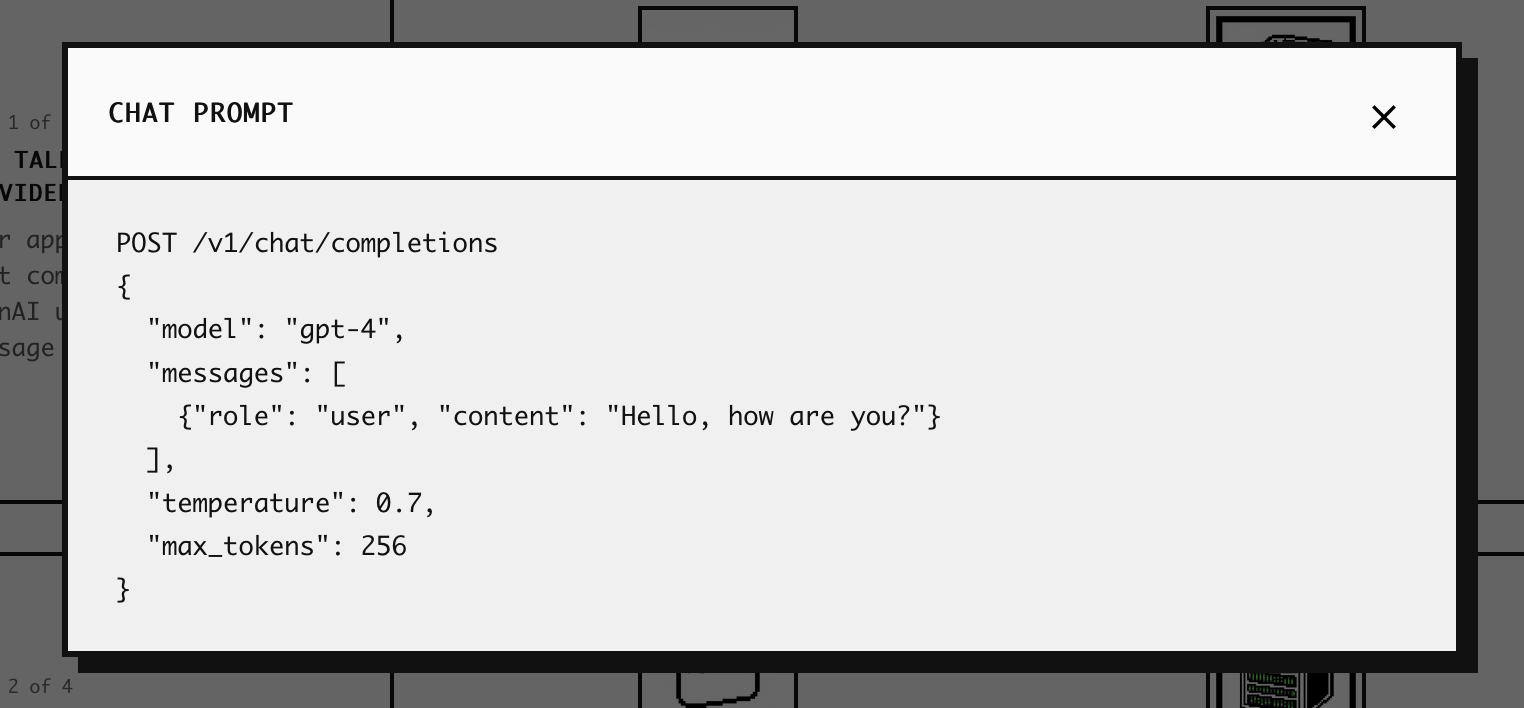

You can click each technology to learn what problem it solves (why did people need something like this?), how it’s standardizing (who kicked this off?), and what virtuous cycle it enabled (why did other people want to get on board?).

You can also see visual animations of how the protocol is used — what messages are actually sent back and forth between who?

If you’re interested in the technical details, you can click any of the messages to see at a wire level what’s actually happening. (Often, something simpler than it sounds.)

As you move off to the right, you’ll go from widely adopted technologies, like MCP, to technologies that have commercial supporters but not much social proof yet, like Visa TAP, or technologies that don’t even exist but might make sense in the future, like Interoperable Memory, Signed Intent Mandates, or Agent Lingua Franca.

The ragged edge on the right is where I hope you’ll be the most critical: what seems inevitable, what seems like a dead end, and what would you like to see more of?

How accurate is all of this? How do I fix mistakes?

APTT is a work in progress, and to be honest in many ways is a whiteboard sketch. I put it together (and vibe coded much of it) to help support a conversation, first at the workshop and now online. I think whiteboard sketches are useful, so I’m sharing it, but I don’t pretend it’s authoritative; it’s just my rough sense of how things work right now.

(This is a weird thing about the agentic moment — my coding agent has made this tool look more polished and complete than it may really deserve. Think napkin sketch with fancy graphics.)

If you think I got things wrong or missed part of the story, please open an issue on the GitHub repository. I plan to keep this rough and opinionated, and focused on consensus-driven protocols as a lens for understanding what’s happening — so I’ll either pull contributions into the main tool, or just leave them as discussions to represent the range of opinions about how all of this works. I hope it’s fun to play with either way.

Weekly Bookmarks / Ed Summers

These are some things I’ve wandered across on the web this week.

🔖 Arke

Arke is a public knowledge network for storing, discovering, and connecting information.

Making content truly accessible is harder than it looks. Meaningful search requires vectors, embeddings, extraction pipelines—infrastructure most people can’t build. And even with that, files sitting on a website or in a folder don’t get found. You end up working alone, disconnected from related work that exists somewhere.

Arke handles all of it. Upload anything—we process it and connect it to a network where similar collections surface automatically. Your information becomes searchable, discoverable, and linked to work you didn’t know existed.🔖 Community Calendar

Public events are trapped in information silos. The library posts to their website, the YMCA uses Google Calendar, the theater uses Eventbrite, Meetup groups have their own pages. Anyone wanting to know “what’s happening this weekend?” must check a dozen different sites.

Existing local aggregators typically expect event producers to “submit” events via a web form. This means producers must submit to several aggregators to reach their audience — tedious and error-prone. Worse, if event details change, producers must update each aggregator separately.

This project takes a different approach: event producers are the authoritative sources for their own events. They publish once to their own calendar, and individuals and aggregators pull from those sources. When details change, the change propagates automatically. This is how RSS transformed blogging, and iCalendar can do the same for events.

The gold standard is iCalendar (ICS) feeds — a format that machines can read, merge, and republish. If you’re an event producer and your platform can publish an ICS feed, that’s great. But ICS isn’t the only way. The real requirement is to embrace the open web. A clean HTML page with well-structured event data works. What doesn’t work: events locked in Facebook or behind login walls.🔖 Engineering Rigor in the LLM Age

🔖 Wikipedia blacklists Archive.today, starts removing 695,000 archive links

The English-language edition of Wikipedia is blacklisting Archive.today after the controversial archive site was used to direct a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack against a blog.

In the course of discussing whether Archive.today should be deprecated because of the DDoS, Wikipedia editors discovered that the archive site altered snapshots of webpages to insert the name of the blogger who was targeted by the DDoS. The alterations were apparently fueled by a grudge against the blogger over a post that described how the Archive.today maintainer hid their identity behind several aliases.

“There is consensus to immediately deprecate archive.today, and, as soon as practicable, add it to the spam blacklist (or create an edit filter that blocks adding new links), and remove all links to it,” stated an update today on Wikipedia’s Archive.today discussion. “There is a strong consensus that Wikipedia should not direct its readers towards a website that hijacks users’ computers to run a DDoS attack (see WP:ELNO#3). Additionally, evidence has been presented that archive.today’s operators have altered the content of archived pages, rendering it unreliable.”🔖 Megalodon (website)

Megalodon (Japanese: ウェブ魚拓, “web gyotaku”) is an on demand web citation service based in Japan.[3] It is owned by Affility.

Megalodon’s server can be searched for “web gyotaku” or copies of web pages, by prefixing any URL with “gyo.tc”; the process checks the query against other services as well, including Google’s cached pages and Mementos.🔖 Exclusive: US plans online portal to bypass content bans in Europe and elsewhere

🔖 How An Academic Library Built a Research Impact and Intelligence Team

🔖 Annotorious

🔖 Potomac Interceptor Collapse

🔖 Inside Claude Code With Its Creator Boris Cherny

🔖 Current

Every RSS reader I’ve used presents your feeds as a list to be processed. Items arrive. They’re marked unread. Your job is to get that number to zero, or at least closer to zero than it was yesterday.

Current has no unread count. Not because I forgot to add one, or because I thought it would look cleaner without it. There is no count because counting was the problem.

The main screen is a river. Not a river that moves on its own. You’re not watching content drift past like a screensaver. It’s a river in the sense that matters: content arrives, lingers for a time, and then fades away.🔖 Phantom Obligation

Email’s unread count means something specific: these are messages from real people who wrote to you and are, in some cases, actively waiting for your response. The number isn’t neutral information. It’s a measure of social debt.

But when we applied that same visual language to RSS (the unread counts, the bold text for new items, the sense of a backlog accumulating) we imported the anxiety without the cause.🔖 ways of working with the Wayback Machine - studio and book talk in Amsterdam

Last week I gave a book talk on Public Data Cultures and co-organised a Wayback studio with the Internet Archive Europe.

As highlighted in the book talk announcement it was really nice to have this moment there given my longstanding collaborations with the Internet Archive - and to meet up with others connected to the archive and associated communities in Amsterdam🔖 Black Jesus

🔖 Oral History of John Backus

Interviewed by Grady Booch on September 5, 2006, in Ashland, Oregon, X3715.2007

© Computer History Museum

John Backus led a team at IBM in 1957 that created the first successful high-level programming language, FORTRAN. It was designed to solve problems in science and engineering, and many dialects of the language are still in use throughout the world.

Describing the development of FORTRAN, Backus said, “We simply made up the language as we went along. We did not regard language design as a difficult problem, merely a simple prelude to the real problem: designing a compiler which could produce efficient programs . . . We also wanted to eliminate a lot of the bookkeeping and detailed, repetitive planning which hand coding involved.”

The name FORTRAN comes from FORmula TRANslation. The language was designed for solving engineering and scientific problems. FORTRAN IV was first introduced by IBM in the early 1960s and still exists in a number of similar dialects on machines from various manufacturers.🔖 FreeBSD Mastery: Advanced ZFS

🔖 disko-zfs: Declaratively Managing ZFS Datasets

Given a situation where a ZFS pool has just too many datasets for you to comfortably manage, or perhaps you have a few datasets, but you just learned of a property that you really should have set from the start, what do you do? Well, I don’t know what you do, I would love to hear about that, so please do reach out to me, over Matrix preferably.

In any case, what I came up with is disko-zfs. A simple Rust program that will declaratively manage datasets on a zpool. It does this based on a JSON specification, which lists the datasets, their properties and a few pieces of extra information.🔖 Level of Detail

🔖 I Sold Out for $20 a Month and All I Got Was This Perfectly Generated Terraform

🔖 Poor Deming never stood a chance

🔖 Emily St. John Mandel

🔖 Deb Olin Unferth

🔖 Citational Politics and Justice: Introduction

🔖 Concatenative language

🔖 Parents are opting kids out of school laptops, returning them to pen and paper

🔖 News publishers limit Internet Archive access due to AI scraping concerns

🔖 Gwtar: a static efficient single-file HTML format

🔖 What technology takes from us – and how to take it back

🔖 Inside Japan’s Most Influential Architect’s Working Studio

Join us for a quiet look inside the workspace of Tadao Ando, offering a brief glimpse into his architectural process.

This studio visit documents the daily rhythms of work and the careful, repetitive making of architectural scale models that sit at the center of his practice. The focus is not on finished buildings, but on process. Time spent refining ideas. Returning to the same forms again and again. Letting work unfold slowly.

Photographed in a restrained, observational way, this project uses still imagery to pay close attention to space, light, and atmosphere. The photographs are not illustrative, but quietly descriptive, allowing the studio to reveal itself as it is.

It is a small window into how creative work happens inside a working architecture studio, and an invitation to slow down and observe the act of making.🔖 Ambient Videos

Toke / Ed Summers

Evan as a skeptic, I will admit, it was interesting to hear about how Claude Code was created and how it is being developed now in this interview with its creator Boris Cherny:

Cherny’s instructions to build for the model they will have in six months, coupled with the seeming lack of understanding of what model they will have in six months (either software development goes away or an ASL-4 level catastrophe) was to be expected I guess? Maybe he knows and just isn’t saying? Maybe there isn’t very good understanding of whether one model is working better than another? The question of how these models are being evaluated for particular types of work, like software development, is actually interesting to me.

Of course, Anthropic employees would like nothing better than for people to forget how to develop software, and to become utterly dependent on them in the process. Indeed they are happily leading the way, high on their own supply of limitless tokens. They are counting on employers to follow suit, paying subscription costs to give their employees tokens to spend instead of having software developers on staff. This is following in the footsteps of what we’ve seen happen with cloud computing.

In some ways this is nothing new. Software developers have been dependent on the centralized development of compilers and interpreters for some time. So you could look at the centralization of software development into platforms like Anthropic and OpenAI as the natural next stage of development in information technology. Indeed, I think this is the argument currently being made (somewhat convincingly) by Grady Booch about a Third Golden Age of Computing which got underway with the rise of “platforms” more generally, and which includes recent genAI platform APIs and tooling.

But the big difference, that they want us all to forget, is the amount of resources it takes to build a compiler compared to an LLM and our ability to reason about them, and intentionally improve them. They also want us to forget that we need to, you know, give them all our data and ideas as context for them to do whatever they want (thanks cblgh). And as with cloud computing, they want us to forget about the materiality of computing, where computation runs. Ironically, I think computer programmers are particularly susceptible to this rhetoric of abstraction, or the medial ideology of the digital and the cloud (Hu, 2015; Kirschenbaum, 2008).

From a sociotechnical perspective I am curious how prompt data is being used to try to improve these models, as people start using them for ordinary tasks, and also in attempts to intentionally shape the model motivated by greed and malice. I guess the details of this process must be well hidden? Pointers would be welcome.

ActiveRecord neighbor vector search, with per-document max / Jonathan Rochkind

I am doing LLM “RAG” with rails ActiveRecord, postgres with the pgvector extension for vector similarity searches, and the neighbor gem. I am fairly new to all of this stuff, figuring it out by doing it.

I realized that for a particular use, I wanted to get some document diversity — so i wanted to do a search of my chunks ranked by embedding vector similarity, getting the top k (say 12) chunks — but in some cases I only want, say, 2 chunks per document. So the top 12 chunks by vector similarity, such that only 2 chunks per interview max are represented in those 12 top chunks.

I decided I wanted to do this purely in SQL, hey, I’m using pgvector, wouldn’t it be most efficient to have pg do the 2-per-document limit?

- Note: This may be a use case that isn’t a good idea! I have come to realize that maybe I want to just fetch 12*3 or *4 docs into ruby, and apply my “only 2 per document” limit there? Because I may want to do other things there anyway that I can’t do in postgres, like apply a cross-model re-ranker? So I dunno, but for now I did it anyway.

So this was some fancy SQL, i was having trouble figuring out how to do it myself, so I asked ChatGPT, sure. It gave me an initial answer that worked, but…

- Turns out was over-complicated, a simpler (to my understanding anyway) approach was possible

- Turns out was not performant, it was not using my postgres ‘HNSW’ indexes to make vector searches higher performance, and/or was insisting on sorting the entire table first defeating the point of the indexes. How’d I know? Well, I noticed it was being slower than expected (several seconds or at times much more to return), and then I did postgres explain/analyze… which I had trouble understanding… so i fed the results to ChatGPT and/or Claude, who confirmed, yeah buddy, this is a bad query, it’s not using your vector index properly.

I had to go on a few back and forths with both ChatGPT and Claude (this is just talking to them in a GUI, not actually using Claude Code or whatever), to get to a pattern that did use my index effectively. They kept suggesting things to me that either just didn’t work, or didn’t actually use the index, etc. I had to actually understand what they were suggesting, and tweak it myself, and have a dialog with them…

But i eventually got to this cool method that can take an arbitrary ActiveRecord relation which already has had neighbor nearest_neighbors query applied to it… and wraps it in a larger query using CTE’s that can limit the results to max-per-document.

I wondered if I should try to share this somewhere (would neighbor gem want a PR?), except… I’m realizing like I said above maybe this is not actually a very useful use case, better to do it in ruby… I’m still not necessariliy getting the performance I expected either, although the analyze/explain says the indexes should be used properly.

So I just share here. Note the original base_relation may be it’s own internal joins to enforce additional conditions on retrieval etc. Assuming each Chunk ActiveRecord model has a document_id attribute which we are using to group for max-per-document.

# We need to take base_scope and use it as a Postgres CTE (Common Table Expression)

# to select from, but adding on a ROW_NUMBER window function, that let's us limit

# to top max_per_interview

#

# Kinda tricky, especially to do with good index usage. Got solution from google and talking

# to LLMs, including having them look at pg explain/analyze output.

#

# @param base_relation [ActiveRecord::Relation] original relation, it can have joins and conditions.

# It MUST have already had vector distance ordering applied to it with `neighbor` gem.

#

# @param max_per_interview [Integer] maximum results to include per interview (oral_history_content_id)

#

# @param inner_limit [Integer] how many to OVER-FETCH in inner limit, to have enough even after

# applying max-per-interview.

#

# @return [ActiveRecord::Relation] that's been in a query to enforce max_per_interview limits. It does

# not have an overall limit set, caller should do that if desired, otherwise will be effectively

# limited by inner_limit.

def wrap_relation_for_max_per_interview(base_relation:, max_per_interview:, inner_limit:)

# In the inner CTE, have to fetch oversampled, so we can wind up with

# hopefully enough in outer. Leaving inner unlimited would be peformance problem,

# cause of how indexing works it doesn't need to calculate them all if limited.

base_relation = base_relation.limit(inner_limit)

# Now we have another CTE that assigns doc_rank within partitioned

# interviews, from base. Raw SQL is just way easier here.

partitoned_ranked_cte = Arel.sql(<<~SQL.squish)

SELECT base.*,

ROW_NUMBER() OVER (

PARTITION BY document_id

ORDER BY neighbor_distance

) AS doc_rank

FROM base

SQL

# A wrapper SQL that incorporates both those CTE's, limiting to

# doc_rank of how many we want per-interview, and overall making sure to

# again order by vector neighbor_distance that must already have been included

# in the base relation.

base_relation.klass

.select("*") # just pass through from underlying CTE queries.

.with(base: base_relation)

.with(partitioned_ranked: partitoned_ranked_cte)

.from("partitioned_ranked")

.where("doc_rank <= ?", max_per_document)

.order(Arel.sql("neighbor_distance"))

end

Like I said, I am new to this LLM stuff, curious what others have to say here.

The Kessler Syndrome / David Rosenthal

|

| LEO in 2019 (NASA) |

It describes a situation in which the density of objects in low Earth orbit (LEO) becomes so high due to space pollution that collisions between these objects cascade, exponentially increasing the amount of space debris over time.This became known as the Kessler Syndrome. Three decades later, shortly after Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251 collided at 11.6km/s, Kessler published The Kessler Syndrome, writing that the original paper:

predicted that around the year 2000 the population of catalogued debris in orbit around the Earth would become so dense that catalogued objects would begin breaking up as a result of random collisions with other catalogued objects and become an important source of future debris.And that:

Modeling results supported by data from USAF tests, as well as by a number of independent scientists, have concluded that the current debris environment is “unstable”, or above a critical threshold, such that any attempt to achieve a growth-free small debris environment by eliminating sources of past debris will likely fail because fragments from future collisions will be generated faster than atmospheric drag will remove them.Below the fold I look into the current situation.

How Likely Is A Kessler Event?

Fast forward another 17 years and Hugh G. Lewis and Donald J. Kessler (in his mid-80s) recently published CRITICAL NUMBER OF SPACECRAFT IN LOW EARTH ORBIT: A NEW ASSESSMENT OF THE STABILITY OF THE ORBITAL DEBRIS ENVIRONMENT. Their abstract states that:Using data from on-orbit fragmentation events, this paper introduces a revised stability model for altitudes below 1020 km and evaluates the March 2025 population of payloads and rocket stages to identify new regions of instability. The results indicate the current population of intact objects exceeds the unstable threshold at all altitudes between 400 km and 1000 km and the runaway threshold at nearly all altitudes between 520 km and 1000 km.This and other recent publications attracted the attention not only of two well-known YouTubers, Sabine Hossenfelder and Anton Petrov, but also of me.

Lewis and Kessler's conclusion mirrors that of the ESA Space Environment Report 2025 from 1st April, 2025 (my emphasis):

The amount of space debris in orbit continues to rise quickly. About 40,000 objects are now tracked by space surveillance networks, of which about 11 000 are active payloads.

However, the actual number of space debris objects larger than 1 cm in size – large enough to be capable of causing catastrophic damage – is estimated to be over 1.2 million, with over 50.000 objects of those larger than 10 cm.

...

The adherence to space debris mitigation standards is slowly improving over the years, especially in the commercial sector, but it is not enough to stop the increase of the number and amount of space debris.

Even without any additional launches, the number of space debris would keep growing, because fragmentation events add new debris objects faster than debris can naturally re-enter the atmosphere.

To prevent this runaway chain reaction, known as Kessler syndrome, from escalating and making certain orbits unusable, active debris removal is required.

|

| Thiel et al Fig. 2 |

While satellites provide many benefits to society, their use comes with challenges, including the growth of space debris, collisions, ground casualty risks, optical and radio-spectrum pollution, and the alteration of Earth's upper atmosphere through rocket emissions and reentry ablation. There is potential for current or planned actions in orbit to cause serious degradation of the orbital environment or lead to catastrophic outcomes, highlighting the urgent need to find better ways to quantify stress on the orbital environment. Here we propose a new metric, the CRASH Clock, that measures such stress in terms of the timescale for a possible catastrophic collision to occur if there are no satellite manoeuvres or there is a severe loss in situational awareness. Our calculations show the CRASH Clock is currently 5.5 days, which suggests there is limited time to recover from a wide-spread disruptive event, such as a solar storm. This is in stark contrast to the pre-megaconstellation era: in 2018, the CRASH Clock was 164 days.They estimate that:

In the densest part of Starlink’s 550 km orbital shell, we expect close approaches (< 1 km) every 22 minutes in that shell alone.For the whole of Earth orbit they estimate the time between < 1 km approaches at 41 seconds.

Will Things Get Worse?

Nehal Malik's Space Is Getting Crowded: Starlink Dodged 300,000 Collisions illustrates the scale of the problem:According to a recent report filed by SpaceX with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, Starlink satellites performed roughly 300,000 collision-avoidance maneuvers in 2025 alone. The figures, first reported by New Scientist, offer a rare look at just how crowded low-Earth orbit has become — and how aggressively SpaceX is managing risk as its constellation scales.While it is true that Starlink is careful:

...

On average, the 300,000 maneuvers worked out to nearly 40 avoidance actions per satellite last year. That number is rising quickly, with estimates suggesting Starlink could be performing close to one million maneuvers annually by 2027 if growth continues at its current pace.

What’s particularly notable is how conservative SpaceX’s approach is compared to the rest of the industry. While the typical standard is to maneuver when the risk of collision reaches one in 10,000, SpaceX reportedly initiates avoidance at a far lower threshold of roughly three in 10 million.Nevertheless Starlink's rate of maneuvers is doubling every six months, which seems likely to force a less conservative policy. The average satellite is moving every 9 days. At this doubling rate, by the end of 2027 the average satellite would move about twice a day.

Starlink currently has over 10,000 satellites, with plans for 12,000 in the short term. I believe the collision probability goes as the square of the number, so that will mean moving on average every 6.25 days. Their eventual plan for 42,000 would mean twice a day, or in aggregate about one move per second.

In order to pump SpaceX/xAI/Twitter stock in preparation for a planned IPO, Musk recently pivoted from cars, weird pickup trucks, self-driving cars, robotaxis, humanoid robots and Mars colonization to data centers in space. He claimed that by 2031 SpaceX/xAI/Twitter would operate a million satellites forming a huge AI data center. Scaling up from the current maneuver rate gets you to about a move every 125ms in aggregate.

How Bad Would A Kessler Event Be?

My friend Robert Kennedy considers the implications of a Kessler event in low Earth orbit:

- Obviously the national security repercussions for the western world, especially the U.S., would be severe with so many force multipliers going away at once. Presenting an opportunity for adversaries to attack us, maybe.

- The overall global space market, presently ~$700B/yr & growing fast, would shrink dramatically. This contraction in turn would be amplified in the world's stock markets since space activity is central to so many Big Tech equities now, and space infrastructure is so deeply embedded many other enterprises' business models. ... Even modest P/E ratios suggest that an order of magnitude more, maybe two (~$10-100T) of paper wealth would disappear.

- The space insurance market would collapse under the burden of covered claims. Re-insurers could not handle so much at once. Companies that chose to self-insure would probably go under after such a casualty. Without insurance, most enterprises could not afford to conduct space missions.

- The space launch market would collapse, leaving only national launch capabilities maintained by individual nations for their individual non-market reasons. All those innovative rocket companies popping up to serve the mega-constellations would go away once their prime customers did. Global launch tempos would fall by more than half, from 200+/yr to well under 100/yr of a generation ago. Forget the $100 per kg that ... Starship was aiming for, price per kilogram would return to what it was 30 years ago, ~$10-20K/kg. Say goodbye to cheap rideshares to LEO. Even running the gauntlet thru LEO would be fraught, as the Chinese learned just a few months ago when their spacecraft was damaged by debris on the way up, necessitating the premature return of the undamaged pre-deployed spaceship to rescue the earlier crew.

- Since 99% of Cubesats fly in LEO, the ecology of COTS parts that has sprung up to serve the Cubesat revolution would probably go away, or back into the garage at least. It might even disappear altogether if authorities of various spacefaring nations ban Cubesats. (Literally "throwing out the baby with the bathwater".) Don't underestimate the inherent conservatism of oligarchs to use a crisis to stomp on upstarts.

Can LEO Be Cleaned Up?

|

| ClearSpace-1 |

What Else Can Go Wrong?

The frenzy to exploit the commons of Low Earth Orbit doesn't just threaten to cut humanity off from space in general and the benefits that LEO can provide. The process of getting stuff up there and its eventual descent threatens to accelerate the process of trashing the commons of the terrestrial environment.Going Up

Elon Musk's proposed one million satellite data center is estimated to require launching a Starship about every hour 24/7/365. Laura Revell et al's Near-future rocket launches could slow ozone recovery describes one problem:Ozone losses are driven by the chlorine produced from solid rocket motor propellant, and black carbon which is emitted from most propellants. The ozone layer is slowly healing from the effects of CFCs, yet global-mean ozone abundances are still 2% lower than measured prior to the onset of CFC-induced ozone depletion. Our results demonstrate that ongoing and frequent rocket launches could delay ozone recovery. Action is needed now to ensure that future growth of the launch industry and ozone protection are mutually sustainable.Black carbon heats the stratosphere, although the increasing use of methane reduces the amount emitted per ton of propellant. Each Starship launch uses about 4000 tons of LOX and about 1000 tons of methane. Assuming complete combustion, this would emit about 1,667 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. So Musk's data center plan would dump about 17 megatons/year into the atmosphere, or about as much as Croatia.

Coming Down

All this mass in LEO will eventually burn up in the atmosphere. Jose Ferreira et al's Potential Ozone Depletion From Satellite Demise During Atmospheric Reentry in the Era of Mega-Constellations describes the effects this will have:This paper investigates the oxidation process of the satellite's aluminum content during atmospheric reentry utilizing atomic-scale molecular dynamics simulations. We find that the population of reentering satellites in 2022 caused a 29.5% increase of aluminum in the atmosphere above the natural level, resulting in around 17 metric tons of aluminum oxides injected into the mesosphere. The byproducts generated by the reentry of satellites in a future scenario where mega-constellations come to fruition can reach over 360 metric tons per year. As aluminum oxide nanoparticles may remain in the atmosphere for decades, they can cause significant ozone depletion.

Can A Kessler Event Be Prevented?

|

| Ozone Hole 10/1/83 |

Due to its widespread adoption and implementation, it has been hailed as an example of successful international co-operation.It has been effective:

Climate projections indicate that the ozone layer will return to 1980 levels between 2040 (across much of the world) and 2066 (over Antarctica).But note that it will have taken almost 80 years from the agreement for the environment to recover fully. And that it appears to be the exception that proves the rule:

effective burden-sharing and solution proposals mitigating regional conflicts of interest have been among the success factors for the ozone depletion challenge, where global regulation based on the Kyoto Protocol has failed to do so.

|

| Source |

In this case of the ozone depletion challenge, there was global regulation already being implemented before a scientific consensus was established.In 1.5C Here We Come I critiqued the attitudes of the global elite that have crippled the implementation of the Kyoto Protocol. I think it is safe to say that the prospect of applying the Precautionary Principle to Low Earth Orbit is even less likely.

...

This truly universal treaty has also been remarkable in the expedience of the policy-making process at the global scale, where only 14 years lapsed between a basic scientific research discovery (1973) and the international agreement signed (1985 and 1987).

🇮🇩 Open Data Day 2025 in Cianjur: Geospatial Data for Mangrove Rehabilitation / Open Knowledge Foundation

This text, part of the #ODDStories series, tells a story of Open Data Day‘s grassroots impact directly from the community’s voices. Bandung Mappers successfully carried out the Open Data Day 2025 activity on March 6 – 8 with the theme Coastal Resilience through Mangrove Rehabilitation which was held in Cianjur, West Java. This activity was...

The post 🇮🇩 Open Data Day 2025 in Cianjur: Geospatial Data for Mangrove Rehabilitation first appeared on Open Knowledge Blog.

🇹🇿 Open Data Day 2025 in Dodoma: Driving Urban Resilience With Open Data / Open Knowledge Foundation

This text, part of the #ODDStories series, tells a story of Open Data Day‘s grassroots impact directly from the community’s voices. The Open Data Day 2025 event in Dodoma brought together open data advocates, government entities, researchers, NGOs, and YouthMappers under the theme “Open Data for a Resilient Dodoma.” Hosted by OpenGeoCity Tanzania with support...

The post 🇹🇿 Open Data Day 2025 in Dodoma: Driving Urban Resilience With Open Data first appeared on Open Knowledge Blog.

🇳🇵 Open Data Day 2025 in Ilam: Co-Creating Solutions to the Polycrisis with Indigenous and Marginalised Communities / Open Knowledge Foundation

This text, part of the #ODDStories series, tells a story of Open Data Day‘s grassroots impact directly from the community’s voices. To celebrate Open Data Day 2025, as part of the Harnessing Opportunities to address Polycrisis through community Engagement (HOPE) project, the Nepal Institute of Research and Communications, in collaboration with the Ilam Municipality, organized a...

The post 🇳🇵 Open Data Day 2025 in Ilam: Co-Creating Solutions to the Polycrisis with Indigenous and Marginalised Communities first appeared on Open Knowledge Blog.

Weekly Bookmarks / Ed Summers

These are some things I’ve wandered across on the web this week.

🔖 theuse.info

🔖 How Etsy Uses LLMs to Improve Search Relevance

Search plays a central role in that mission. Historically, Etsy’s search models have relied heavily on engagement signals – such as clicks, add-to-carts, and purchases – as proxies for relevance. These signals are objective, but they can also be biased: popular listings get more clicks, even when they’re not the best match for a specific query.

To address this, we introduce semantic relevance as a complementary perspective to engagement, capturing how well a listing aligns with a buyer’s intent as expressed in their query. We developed a Semantic Relevance Evaluation and Enhancement Framework, powered by large language models (LLMs). It provides a comprehensive approach to measure and improve relevance through three key components:

High quality data: we first establish human-curated “golden” labels of relevance categories (we’ll come back to this) for precise evaluation of the relevance prediction models, complemented by data from a human-aligned LLM that scales training across millions of query-listing pairs Semantic relevance models: we use a family of ML models with different trade-offs in accuracy, latency, and cost; tuned for both offline evaluation and real-time search Model-driven applications: we integrate relevance signals directly into Etsy’s search systems enabling both large-scale offline evaluation and real-time enhancement in production🔖 Understanding Etsy’s Vast Inventory with LLMs

While our powerful search and discovery algorithms can process unstructured data such as that in descriptions and listing photos, passing in long context and images directly to search poses latency concerns. For these algorithms, every millisecond counts as they work to deliver relevant results to buyers as quickly as possible. Spending time filtering through unstructured data for every query is just not feasible.

These constraints led us to a clear conclusion: to fully unlock the potential of all inventory listed on Etsy’s site, unstructured product information needs to be distilled into structured data to power both ML models and buyer experiences.🔖 Unlocking the Codex harness: how we built the App Server

OpenAI’s coding agent Codex exists across many different surfaces: the web app(opens in a new window), the CLI(opens in a new window), the IDE extension(opens in a new window), and the new Codex macOS app. Under the hood, they’re all powered by the same Codex harness—the agent loop and logic that underlies all Codex experiences. The critical link between them? The Codex App Server(opens in a new window), a client-friendly, bidirectional JSON-RPC1 API.

In this post, we’ll introduce the Codex App Server; we’ll share our learnings so far on the best ways to bring Codex’s capabilities into your product to help your users supercharge their workflows. We’ll cover the App Server’s architecture and protocol and how it integrates with different Codex surfaces, as well as tips on leveraging Codex, whether you want to turn Codex into a code reviewer, an SRE agent, or a coding assistant.🔖 OpenAI and Codex with Thibault Sottiaux and Ed Bayes

AI coding agents are rapidly reshaping how software is built, reviewed, and maintained. As large language model capabilities continue to increase, the bottleneck in software development is shifting away from code generation toward planning, review, deployment, and coordination. This shift is driving a new class of agentic systems that operate inside constrained environments, reason over long time horizons, and integrate across tools like IDEs, version control systems, and issue trackers.

OpenAI is at the forefront of AI research and product development. In 2025, the company released Codex, which is an agentic coding system designed to work safely inside sandboxed environments while collaborating across the modern software development stack.🔖 Tetragrammaton: George Saunders

🔖 Little Atoms - 2 February 2026 (George Saunders)

🔖 Bridging the Data Discovery Gap: User-Centric Recommendations for Research Data Repositories

Despite substantial investment in research data infrastructure, data discovery remains a fundamental challenge in the era of open science. The proliferation of repositories and the rapid growth of deposited data have not resulted in a corresponding improvement in data findability. Researchers continue to struggle to find data that are relevant to their work, revealing a persistent gap between data availability and data discoverability. Without rich, high-quality metadata, robust and user-centred data discovery systems, and a deeper understanding of how different researchers seek and evaluate data, much of the potential value of open data remains unrealised.

This paper presents a set of practical, evidence-based recommendations for data repositories and discovery service providers aimed at improving data discoverability for both human and machine users. These recommendations emphasise the importance of 1) understanding the search needs and contexts of data users, 2) addressing the roles that data repositories play in enhancing metadata quality to meet users’ data search needs, and 3) designing discovery interfaces that support effective and diverse search behaviours. By bridging the gap between data curation practices, discovery system design, and user-centred approaches, this paper argues for a more integrated and strategic approach to data discovery.🔖 blevesearch

🔖 hister: Web history on steroids

🔖 Alphabet sells rare 100-year bond to fund AI expansion as spending surges

🔖 The Eternal Mainframe

In the computer industry, the Wheel of Reincarnation is a pattern whereby specialized hardware gets spun out from the “main” system, becomes more powerful, then gets folded back into the main system. As the linked Jargon File entry points out, several generations of this effect have been observed in graphics and floating-point coprocessors.